This is a follow-up to an earlier post, "On Being Joan".

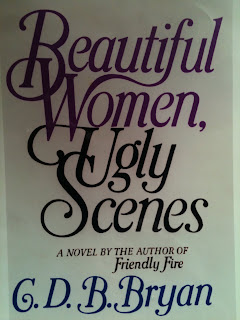

The first hit came in the New York Times Book Review. By the time Alice Adams called Dad's narrator "a very confused little boy, and this is a very confused long book", she'd already made Beautiful Women; Ugly Scenes look ridiculous with this paragraph:

Not only are all the women beautiful, they are all under 35, and none of them have aspirations toward professions or even jobs until under duress. They have, however, wonderful breasts, some huge: "When we made love they would flow, crest upward, break across her chest like waves, like surf." But most of the many, many breasts in this book are shaped like tears, a conceit that I have not come across before:" I was admiring their breasts, their weight, their arc as they flowed in a giant teardrop around their rib cages and then disappeared under their arms" (The confusion in syntax here led me to believe for a moment that he liked heavy women--at least an original taste--but not so; he likes heavy breasts.) Odette, the final great love, has breasts with nipples that remind the narrator of the noses of small puppies.

Dad would be told later than Adams had recently had a masectomy.

The review meant Dad would have to work harder to promote his book. More radio shows. More interviews. In Chicago he did twelve interviews in 32 hours. In New York, one morning, he did Morning Edition for NPR, followed immediately by Weekend Edition and then All Things Considered with a break for lunch ...with a reviewer.

The questions eventually came around to the one he hated. How much of Beautiful Women; Ugly Scenes is based on his real life.

As the LA Herald Examiner's Carol A Crotta put it.

The book is more than vaguely autobiographical. The narrator has been divorced twice; so has Bryan. The narrator picks up money during slow times by teaching in colleges; so does Bryan. The narrator has Odette; the woman in Bryan's lifde the past six years is Monique.

The obvious parallels are "very deliberate," he said, and they invite personal questions. "I don't mind you asking questions about it," he responds immediately, "as long as I don't have to answer them."

...And yet the lines between the narrator and Bryan blur often enough to cause some confusion even to members of Bryan's family. The eldest of Bryan's two daughters read the book, and Bryan relates,"There was sort of an awful 20 minutes where I really had to sit her down and say 'Look, Joan is not you and this is why she's not you' She could not read about Joan in the book without thinking it was her."

Soon Dad had a stock answer for the question: The book is 80% less autobiography than readers would like to think and 20% more than I would like to admit.

But as he would write later:

It's an answer that seems to satisfy (interviewers). But I have no idea what that answer really means. Nor do I think the question of autobiography in fiction has any literary relevance whatsoever. It may be an interesting question in terms of gossip, but not as related to books.

Dad complained most reviewers missed the point of the book. To those like Adams, he wanted to point out that he was using a literary device known as the unreliable narrator (like Humbert Humbert in Lolita or Spacey's character in The Usual Suspects.)

As he told a local newspaper reporter: "I knew what an ass he was or I wouldn't have written the book."

His hopes that he had a best seller on his hands soon vanished. No movie companies came calling. His next book would be one he'd have to do strictly for the money.

No comments:

Post a Comment